January 30, 2019

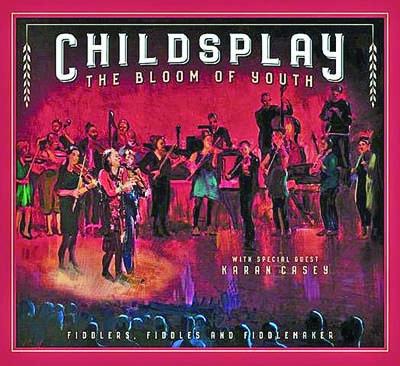

Childsplay, “The Bloom of Youth” • Hard not to feel bittersweet about the latest release by this all-star fiddle ensemble, because it heralds the end of a grand two-decades-plus partnership.

Childsplay comprises two dozen or so musicians – many from Boston or elsewhere in New England – performing fiddle music mainly from Irish, Scottish, Cape Breton, Scandinavian, French Canadian, and American folk traditions. All the fiddlers use violins created by Cambridge resident Bob Childs, who also plays in the band and serves as its artistic director, as well as its namesake. Almost every fall, the group has gathered – albeit not always with the same exact roster – to put together new material and go on a brief tour, which typically includes a stop at the Somerville Theater.

In 2017, Childs announced that the ensemble would go on hiatus, record its seventh album, return to the stage in 2018, and then embark on one final tour this coming fall. So, “The Bloom of Youth” amounts to the last recorded testament of Childsplay (viral or official videos aside) – and it is a fine and fitting farewell.

As before, the brilliancy of fiddlers like Laurel Martin, Hanneke Cassel, Lissa Scheckenburger, Sheila Falls, Amanda Cavanaugh, and Childs himself, plus other exceptional musicians like Shannon Heaton (flute, whistle), Kathleen Guilday (harp), Keith Murphy (guitar, piano), and Mark Roberts (banjo, bouzouki, whistle, percussion), as well as vocalist Karan Casey, is enriched by their arrangements, whether the full ensemble or various components of it. The instrumental sets and songs are full of dramatic builds, gentle interludes, suddenly energetic passages, offsetting rhythms and counterpoints.

The titular track and reel begins with Murphy’s groove-steady piano and an equally stellar banjo accompaniment by Roberts as fiddles – and the superb cello-playing of Elsie Gawler and McKinley James – take up the melody; then the tempo ratchets up with the E-minor reel “Temple House” – just a handful of fiddles set against Roberts’ banjo – until the full assemblage cruises onto the Charlie Lennon composition “Sailing In.” Cassel and Murphy (on guitar) lead on a Cape Breton/Scottish set, starting out with a good-and-punchy “Buddy’s Strathspey” — her tribute to the legendary Cape Breton fiddler Buddy MacMaster; Heaton, on flute, takes over on the reel, “Wooden Whale,” by Alasdair Fraser, and the track climaxes with “The Farmer’s Daughter,” full of drop-dead gorgeous harmonies. Another track combines Falls’ winsome “Lara’s Jig” (named for her older daughter), with fiddles trading off on melody and chords; a Johnny McCarthy composition, “The Burning Snowball,” marked by Guilday’s deft harp-playing; and a blazing denouement with Armagh fiddler Brendan McGlinchey’s “Farewell to London.”

And to show that they’re a fun bunch, they have a go at “Turka,” a bit of Russian gypsy jazz led by Bonnie Bewick with all the appropriate melodrama and pyrotechnics – she even references “Orange Blossom Special”-style rhythmic chopping and bowing.

Then there’s the singing of Casey, who has served as Childsplay’s vocalist for the past couple of years; while her predecessors, Scheckenburger and Aoife O’Donovan, each have much to credit them, Casey provides a whole other dynamic, with her background in Irish tradition and sheer passion. She’s recorded “Sailing Off to Yankeeland” – a particularly moving famine/emigration song associated with the great Frank Harte – in her partnership with John Doyle, but the Childsplay setting is sumptuous in its expression of sorrow and bitterness: empathetic strings, Murphy’s discreet piano, Heaton’s solitary whistle, and Casey’s soaring, emotive delivery. She also does plenty of justice to the archetypal dandling song “Cucanandy,” and the late Andy M. Stewart’s “Where Are You Tonight, I Wonder?” and puts her own sweetly elegiac “Lovely Annie” – written on the death of her mother – into the Childsplay mix, all with splendid results.

Of further interest is the Casey/Childsplay take on “The Fiddle and the Drum,” the Vietnam-era anti-war song which might prove to be Joni Mitchell’s most enduring and profound creation: As Casey intones the song’s message of locating humanity within putative enemies (“But I can remember/All the good things you are/And so I ask you please/Can I help you find the peace and the star”) Bewick’s arrangement employs a series of long, bowed notes from a subset of the ensemble, ominous one moment and reassuring the next. It’s a reminder that Childsplay, inspired by music traditions and styles that go back centuries, is thoroughly modern and forward-looking in its collective vision. They’ll be missed. [childsplay.org]

Ímar, “Avalanche” • This quintet takes its name from the ninth-century Viking who founded a great dynasty in Ireland and Scotland, which would seem quite appropriate for a band that has ties, musical and otherwise, to both places. And listening to them, there might be a temptation to say that Ímar’s music displays the ferocity attributed to those Norse warriors. But that’s going a little overboard: It takes prodigious control and skill to play with the intensity Ímar does and sound as high-quality as they do. And it’s clear that these guys have all that and more.

“Avalanche” is the second album by the band, whose members – Adam Brown (bodhran, guitar), Ryan Murphy (uilleann pipes, flute, whistle), Tomás Callister (fiddle), Adam Rhodes (bouzouki) and Mohsen Amini (concertina) – are from Ireland and various parts of the UK, including the Isle of Man, and now based in Glasgow. They originally met as teenagers through Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann (a pretty darn good endorsement for CCÉ) and have played with highly praised bands like Talisk, Cara and RURA. Murphy’s pipes, by their very nature, are the most conspicuous melodic feature of Ímar, but Amini’s flat-out phenomenal concertina-playing is the sinew of the band – which is not to overlook Callister’s energetic fiddling. Brown’s bodhran, meanwhile, helps power things along but rides ably along in the sidecar on the more moderate-tempo numbers, and Rhodes’ bouzouki bolsters Ímar’s rhythmic heft.

Most of the material on “Avalanche” is self-composed or by other contemporary musicians, and while solidly in the traditional vein, a modern mindset is discernible here: harmony, syncopation, improvisatory passages or bridges, such as on “White Strand,” and rock-style grooves (albeit with acoustic instruments). If you’re looking for the characteristic Ímar track, try “Rambling,” a robust trio of slides that climaxes with “Dilly Dilly” (hopefully not a reference to a certain beer commercial) and a pulse-quickening variation in the B part executed by Amini and Murphy. Or “Blue,” a threesome of reels that scarcely lets up for a second (listen to the changing rhythm pattern on the middle tune, “Spiders”). Or the polka medley “Wise” – Brown and Rhodes are in particularly fine form here, and there is a lovely bit of harmony between Amini, Murphy and Callister during “John Creeney’s.”

Adding to the delights of “Avalanche” is the production of Donald Shaw, who in addition to some stints on electric piano put together arrangements for the string quartet that appears on various tracks. Greg Lawson and Fiona Stephens (violins), Rhoslyn Lawton (viola) and Sonia Cromarty (cello) provide strokes, counterpoints and fills that deepen and broaden without distracting from the core sound, such as on “White Strand,” the first of three successive tracks (along with “Afar” and “Setanta”) that showcase Ímar’s quieter, more lyrical persona.

There’s something satisfying about the album’s closing track, the traditional reels “Sally Reel/Dunrobin Castle/Dunmore Lasses.” It amounts to a we-know-from-whence-we-come statement by the band, reminding us (as if needed) that innovation and experimentation do not by definition sever the bond with tradition. [www.imarband.com]

Salt House, “Undersong” • The second release from this Scottish band, originally a quartet and now a trio of Ewan MacPherson (guitars, vocals) – who also plays with Shooglenifty – Lauren MacColl (fiddle, viola, vocals) and newest member Jenny Sturgeon (guitar, harmonium, vocals). They blend an assortment of contemporary acoustic styles, such as 1960/70s UK blues-folk a la Pentangle and introspective, pastoral songwriting informed by the likes of Frost – including a moody setting of his “The Road Not Taken” – and Burns, whose “Westlin Winds” provided inspiration for Sturgeon’s “Charmer”; similarly, “Old Shoes” is an ode to perambulation, while “Staring at Stars” is a quietly stirring acclamation for locating one’s sense of place and self.

Throughout is a deep appreciation for the folk song and literary tradition, such as “Turn Ye to Me” – a supernatural tale of bereavement from 19th-century poet John Wilson – and an intriguing, minor-key rework of “I Sowed Some Seeds.” The album’s centerpiece is “The Sisters’ Revenge,” based on a Scandinavian murder ballad collected and translated by 19th-century writer Robert Buchanan: Exquisitely, perfectly arranged and paced, the trio patiently unfolds the grim, gritty narrative with its chilling refrain (“The summer comes, the summer goes/On the grave of my father, the green grass grows”).

Much to applaud here, notably the instrumental interplay between MacColl and MacPherson, the quality of the writing, and above all the outstanding vocals, whether among all three, as on “The Sisters’ Revenge,” or individually – most especially Sturgeon’s clear, cogent delivery. Word is Salt House will be at work this year on a new release, and this is an event that merits anticipation. [“Undersong” is available via download at salthouse.bandcamp.com/album/undersong; the band's website is www.salthousemusic.com]