September 8, 2021

Niamh Ní Charra, “Donnelly’s Arm” • When she’s not playing fiddle or concertina, or singing in Gaelic or English, Killarney native (and one-time “Riverdance” musician) Ní Charra toils as a professional archivist. If that summons up images of somebody spending long hours combing through dusty tomes or obscure, archaic objects in dimly lit rooms, you might consider that the work of folks like her – according to the Society of American Archivists – “serves to strengthen collective memory [and] protect the rights, property, and identity of citizens.” A keen appreciation of history, and the ability to engage others through imaginative, thought-provoking interpretation of archival material are often cited as highly useful qualities for the job.

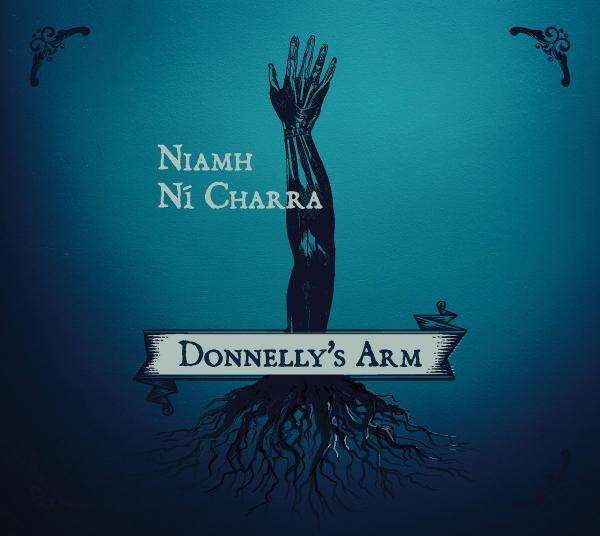

In that light, Ní Charra certainly seems to have effectively melded her callings as archivist and traditional music performer. Her 2013 album “Cuz” (on which she was joined by Liz Carroll, Jimmy Keane, Seamus Begley, and Mick Moloney, among others) was a tribute to Kerry-born Chicago-based musician Terry “Cuz” Teahan, and included excerpts from a cassette tape he’d made for her as well as liner notes that offered useful, and fun, details on the music and its place in Teahan’s life. Here, the album title – also the name of a reel Ní Charra composed – offers further evidence that she knows a good (if macabre) story when she hears one, and can derive inspiration from it in more than a few ways.

Most importantly, though, Ní Charra once again has made a fine recording that is distinguished by excellent musicianship, some really good ideas, and the general joie de vivre that seems to suffuse her body of work. Her versatility on fiddle and concertina are at the forefront, of course, but leaves plenty of room for her core accompanists, Kevin Corbett (guitars) and Dominic Keogh (bodhran), and other guest musicians. While firmly rooted in traditional Irish music, she’s not at all hesitant about exploring beyond it.

Consider the opening track, a trio of jigs that begins with Corbett laying down a gentle arpeggio, supplemented by Keogh, until Ní Charra enters on fiddle with the moderate-speed “The Copper Mines of Killarney,” which she composed, full of lovely swoops and slides; when she gets to the tune’s B part, Corbett shifts into a chordal, jazzy backing that helps set up the transition into Diarmaid Moynihan’s “Covering Ground” – Ní Charra and Corbett doubling on melody in the B part – and then Keogh and Corbett fire up the engines for Ní Charra’s dandy rendition of a jig associated with, and named for, Métis fiddler Andy de Jarlis (although often lumped in with the Nova Scotia/Cape Breton tradition).

A set of reels combines Tony Sullivan’s intense, D-mixolydian “The Exile of Erin”; “Richie Dwyer’s” (the Cork accordionist) – Ní Charra switches from fiddle to concertina for this one; another Ní Charra original, “Red-Haired Catherine,” which memorializes World War II Irish heroine and Belgian resistance fighter Catherine Crean; and an ebullient French-Canadian number, “Ril Du Forgeron,” with Claire Sherry’s banjo adding punch.

Elsewhere, an agile Basque melody, “Amaitzeko Soñu,” on concertina (learned from Basque musician Ibon Koteron, with whom she recorded in 2009) leads into a trio of polkas, including the classics “As I Looked East and I Looked West” and “The Glen Cottage,” and then yet another Ní Charra piece, “I Will, Yeah” – yes, her liner notes explain the meaning of the phrase.

For the album’s eponymous tune, Ní Charra drew on the legend of 19th-century Dublin boxer Dan Donnelly, whose right arm became a well-traveled memento after his death (she heard the story at a Dublin pub originally opened by Donnelly). She follows with two well-known reels, “Pretty Peggy” and “Julia Delaney’s,” assisted by Sherry and flute/whistle player Órlaith McAuliffe.

Ní Charra’s trad roots really come to the fore on the air “Eanach Dhúin,” the melody taken from a song commemorating a tragic event in 1828 Galway. The track highlights her masterful control of the concertina – it’s often said the true test for an Irish musician is playing the slow tunes, not the fast ones – and ability to transmute the instrument’s often raucous sound to one more hushed and plaintive. Adding to the depth, and emotionality, of the tune is cellist Kate Ellis.

The album’s three songs, two of them in Gaelic, also make for an intriguing mix. “Cad é Sin Don t’É Sin,” from the repertoire of South Kerry sean-nos singer Mícheál Ua Duinnín – Ní Charra describes the song as being “from the point of view of someone who probably likes his cider a little too much but is unconcerned what others might think” – is propelled along by Corbett’s relentless multi-tracked guitars and Keogh’s bodhran. Uilleann piper Mikie Smyth joins Ní Charra for “Ceoil an Phíobaire,” a beautiful-in-all-its-melancholia lament of (fittingly enough) a piper for the object of his unrequited affections.

The third is “Gone, Gonna Rise Again,” one of American singer-songwriter/activist Si Kahn’s best-known and most deservedly popular creations, a reminder of the bond that exists – however little appreciated or acknowledged these days – between generations: “I think of my people that have gone on/Like a tree that grows in the mountain ground/The storms of life have cut them down/But the new wood springs from roots in the ground.” It’s a song that doesn’t require a rabble-rousing delivery, and Ní Charra sings it with appropriately quiet resolve, and yet more outstanding work by Corbett in helping lend a bluesy disposition; a composition of Ní Charra, “Ar Scáth a Chéile” follows, played as both a slip jig and reel, with Sherry on banjo – the tune’s title refers to an old Irish proverb about interdependence and caring for one another, dovetailing very well with Kahn’s lyrics.

That aphorism also appears in the album’s liner notes, accompanying Ní Charra’s dedication to those on the front lines battling COVID, and those who have perished from the disease. You don’t necessarily have to be an archivist to lend that kind of context, but it sure doesn’t hurt – and if you’re a superior musician and singer, all the better. [niamhnicarra.com]