December 1, 2016

Understand, it’s not as if Aodán Coyne and brothers Shane and Fiachra Hayes – known collectively as “Socks in the Frying Pan” – had some grand scheme to become one of the most in-demand Irish bands to make the trek to America.

Understand, it’s not as if Aodán Coyne and brothers Shane and Fiachra Hayes – known collectively as “Socks in the Frying Pan” – had some grand scheme to become one of the most in-demand Irish bands to make the trek to America.

For a good while, they were quite content to play in and around their native Ennis in Co. Clare. But through a succession of happy events, and the requisite hard work, the three – ranging in age from 25 to 30 – saw their popularity mushroom, culminating in their first American tour in 2014. They’ve returned to the US twice since then, including a visit this year that brought them for the first time to The Burren in Somerville, where they performed in the early fall to a full house as part of the pub’s Backroom series.

“It all just came out of nowhere,” said Coyne, as he and the Hayeses relaxed prior to the show, reflecting on the last couple of years. “We made an album pretty much for the sake of making it – so we’d have something to sell in the pubs – and it found its way into the right hands. Then when we got over here, we met all these bands and performers we’d looked up to, and we got to tour and play together on the same stages. And that just got everything rolling.”

It’s not hard to discern why they’ve become so popular among audiences, in the US and elsewhere: tip-top musical ability by all three – Coyne on guitar, Shane on accordion, and Fiachra on fiddle and banjo – and polished, sweet-voiced singing to match, plus a stage presence that rides on showmanship, humor, and, above all, an ability to connect with audiences.

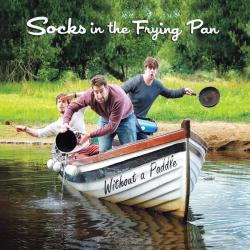

These virtues are certainly apparent on their most recent album, “Without a Paddle,” released earlier this year. The instrumental sets are invigorating, and illustrative of the trio’s traditional roots, as evidenced by “113.5874” (many of their set titles are in-jokes or amusingly self-referential) comprising the reels “John O’Dwyer’s/Maids of Castlebar”; “No Relation,” which combines a Scottish strathspey, a reel from Cape Breton and another from the repertoire of Clare fiddle doyen Martin Hayes; and “Little Red Rocket,” a bracing trio of jigs that climaxes with the regal “Sweet Marie” (a favorite of the Hayeses’ grandmother).

Their song repertoire ranges far afield, from the traditional “When First I Came to Caledonia” to singer-songwriters like Americans Ricky Skaggs (“How Mountain Girls Can Love”), Guy Clark (“Dublin Blues”) and Joe Newberry (“Missouri Borderlands”) and Irish performer Foy Vance (“Guiding Light”). Coyne’s honeyed, charismatic inflection, delivery, and tone, along with the equally charming harmony vocals of the Hayeses, are very much in keeping with the contemporary folk vein of Irish bands like Grada or We Banjo 3. (Boston-area progressive bluegrass/Americana band Crooked Still is a favorite, according to Fiachra.)

And their sense of fun also comes through to a certain degree on “Without a Paddle,” such as Coyne’s funk-flavored riff underneath Shane on “Distraction Tactics,” a tune by American flutist Nolan Ladewski that opens the “Funky In Theory” set; Shane and Fiarach’s flourishes on the aforementioned “Sweet Marie”; and the pregnant pause (and daffy coda) at the end of the “Angry Bees” set.

The Burren concert, though, offered the fullest portrait of Socks in the Frying Pan, including not only their artistry but their flair for entertainment. Coyne’s voice was in fine form, as was his guitar accompaniment, and as a bonus he played on a set of tunes with his fiddle-playing uncle Eamon, a Massachusetts resident. Shane, meanwhile, did a solo spot in which he announced his intention to get an entry in the Guinness Book of World Records “for having the fastest fingers,” and proceeded to play that much-exalted reel “The Mason’s Apron” at ever-increasing speeds. The Hayes brothers also indulged in their good-natured sibling rivalry, trading quips about everything from their respective wardrobes to their musical abilities (during Shane’s accelerating accordion solo, Fiachra remarked, “I can finish it for you if you want”).

As they revealed in the pre-concert conversation, the Hayes’ musical co-dependence started very early on, when Shane decided he’d teach Fiachra – who could barely walk yet – how to play the piano in their grandmother’s sitting room, and helpfully drew numbers on the keys with a magic marker to make it easier for his little brother to get the notes right.

“Then he tried to blame it on me,” said Fiachra, “even though I didn’t know what numbers were yet.”

“And because it was a permanent marker,” added Shane, “the numbers were still there on the keys years later.”

But when it comes to formative musical experiences, the ones they’ve had these past few years have been considerable.

“That first tour, we went over very innocent, not really knowing what we were doing,” said Shane. “But it was cool, and we seemed to take to it naturally, I suppose.”

“You have to latch on pretty quickly,” added Coyne. “When you get to a festival, you see all these bands who’ve been on the circuit for ages, and they just know how to interact with an audience – that’s something you really pick up on when you’re starting out.”

One of the most important lessons they learned was how to fashion one’s act for different kinds of venues. “The big festivals are great: It’s such a cool atmosphere, when you’re playing for 5,000, 6,000 people and there’s such a lot of energy going around,” said Shane. “But the gigs in smaller places, where it’s 70, 80, maybe 100 people, those are lots of fun in a different way. You can get away with more stuff, do more chatting, and there’s not as much pressure to ‘do a performance’; you can be more relaxed about it.”

However irreverent they may seem at times, Coyne, Shane, and Fiachra understand very well that they’re part of a continuum in Irish music, and express a sincere appreciation for the many individuals and bands that have served as role models and sources of inspiration.

“If you just look around here,” said Shane, indicating The Burren’s massive collection of assorted flyers, posters and photos of Irish music’s most renowned figures, “you can see who we looked up to.”

“I love the gigs in places that have a history to them, like here,” said Fiachra. He nodded at a drawing, mounted on the nearby wall, depicting scenes in Ennis. “I can see some of the pubs where we used to play,” he said, and then pointed to a poster on another wall. “And that pub right there? That’s where we got our start. The same poster is up in that pub – it’s the only other place I’ve ever seen it. There really is a lot of history on these walls.”