February 27, 2019

The accompanying article was first published in the Boston Irish Reporter in the summer of 2004. Its focus was a new book by Susan Gedutis that spoke to a time in the city’s history when Irish music and dance had plenty of spaces in which to flower and plenty of participants eager to listen and take to the floor.

Today, the author, now Susan (Gedutis) Lindsay, and her husband Stephen, a Dublin native, performing as “The Lindsays,” are well known for delighting audiences with music that deeply honors the Irish folk tradition while also reflecting who they are and where they have been.

With Susan playing sax, Irish flute, and whistle, Stephen playing guitar and singing, and Ted Mello joining them on upright brass in their full-band configuration, the team’s menu of contemporary songs, old ballads, and traditional Irish jigs and reels has long been a favorite with Irish music lovers up and down the Massachusetts coast.

From the 1940s to the mid-1960s, Boston’s Dudley Square pulsated with the rhythms of Ireland. For the Boston Irish, the dance halls of Roxbury were the places to meet, mingle, and, in many cases, find one’s future spouse. Those postwar decades were the Golden Era of Irish music and dance in these parts, and even today, men and women who danced to the finest Irish bands and musicians of the era grow misty-eyed at cherished memories of the time when everyone knew what the words “see you at the hall” meant.

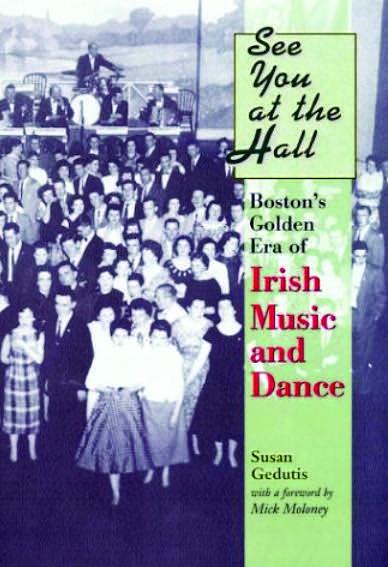

Author Susan Gedutis set out to explore the impact that the Irish dance halls had both musically and culturally in the region, and her efforts have resulted in a finely crafted work entitled “See You at the Hall: Boston’s Golden Era of Irish Music And Dance.” The book not only covers the amazing array of musicians who performed at the famed venues — the Intercolonial, the Hibernian, Winslow Hall, the Dudley Square Opera House, the Rose Croix – that filled Dudley Square with song and dance, but it also captures the sights, sounds, and emotions of the people who gathered at the halls to hear their favorite performers and to meet each other.

Through interviews with men and women for whom the dance halls were social settings where they could establish connections with newfound friends and, in the case of immigrants, could find a connection with the music of the land they had left, Gedutis has crafted a history that resonates with the voices and recollections of the people who were there.

Gedutis is eminently qualified to have taken on the history and meaning of the Dudley Square dance halls. A music book editor at Berklee Press, the publishing arm of Berklee College of Music in Boston, she is also an accomplished player of traditional Irish flute and whistle, along with the alto and baritone saxophones. She teaches music and performs regularly in clubs, pubs, and at dances in the New England area.

Fittingly, her book’s foreword is rendered by Mick Maloney, the renowned Irish singer and instrumentalist, as well as the author of Far From the Shamrock Shore: The Story of Irish-American Immigration through Song.

Thursday and Saturday nights were the big draws of the halls, and, as Gedutis points out, the Boston Irish found the dances and socials “a bridge from the old world to the new.” With ample reason, the social scene of the Dudley Square dance halls led to Boston’s status as the “American capital of Galway.” Irish and Irish Americans turned out literally by the thousands to crowd the halls, and with Gedutis’s fine prose serving as an historical tour guide, the reader views the social scene from the dance halls’ heyday to their decline in the 1960s. The boom years were the post-World War II years and the 1950s; then, as immigration waned in the 1960s and as Roxbury’s demographics changed, the glory days of Roxbury’s Irish dance halls ebbed. Still, even after the last dance hall closed, the musicians kept playing - but in a reduced form at pubs, social clubs, and private parties, all of which allowed Boston’s Irish music scene to endure and enjoy a major revival in the 1990s to the present day.

Recently, Susan Gedutis discussed her book and the place of the dance halls in the over-arching saga of the Irish Diaspora.

BIR: What ignited your interest in writing a book about Boston’s Irish dance halls?

Gedutis: It began in one way as part of my master’s thesis about four years ago. But an event that really drew me to the subject was a 1999 lecture by Joe Derrane, the great Irish accordion player, in Watertown. His vivid and colorful recollections and anecdotes about the golden days of the halls – the overflow crowds, the endless gigs, the way in which so many people met their future spouses there, the sheer joy and nostalgia of it all — hooked me. Also, as a saxophone player who was learning to play traditional Irish flute and tin whistle, I was thrilled to discover that saxophones were a part of the dance hall days - not just the traditional Irish instru-

BIR: In researching the book and especially in your interviews of so many of the dance halls’ patrons and musicians, did you discover anything that really surprised you?

Gedutis: I gained so many insights about what Irish music meant – and means - to people in Boston. Boston really is close to Ireland in so many ways, and the music is one of those ties. People’s eyes light up when I ask them about the dance halls and the music. Widows and widowers tell me all about how they met the love of their lives at the halls.

BIR: Of all the Dudley Square dance halls, which one did you find held “flagship” status?

Gedutis: They all had their fans and their unique look, but there’s no doubt that the showpiece was the Intercolonial. It was the most popular. So many people have said to me, “I danced there the Intercolonial] to Johnny Powell.” He was one of the best talented, charismatic, and had a great band.

BIR: When the halls shut their doors for the last time, what was the impact upon the musicians?

Gedutis: They kept playing, but in much smaller venues such as the pubs and smaller halls. The main thing was they kept playing - they never put their instruments away. That’s why the music remained on the scene in Boston and paved the way for a big revival. Thanks to people such as Larry Reynolds, so much music and dance remained alive.

BIR: What would you most like for readers to take away from the book?

Gedutis: The fact that Irish music has long been part of Boston, and never more so than in the days of the dance halls and at the present time. There is a genuine and vibrant historical precedent for the local Irish music scene today. It makes people realize that they were part of this historic and cultural tradition of Irish music and dance. Speaking for myself, researching and writing the book proved an emotional experience. I met some truly wonderful people for whom the Irish Dance halls of Dudley Square were a joyous and defining period of their lives, as well as that of Boston.

(See You at the Hall: Boston’s Golden Era Of Irish Music And Dance, by Susan Gedutis, Northeastern University Press.