October 31, 2019

By Sean Smith

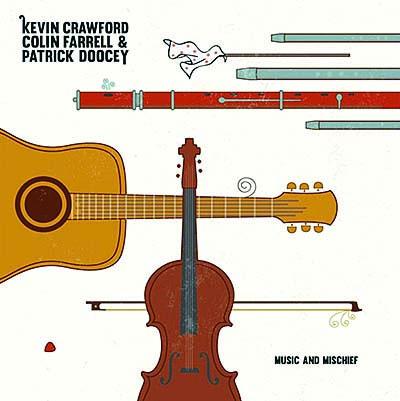

Kevin Crawford, Colin Farrell and Patrick Doocey, “Music and Mischief” • One of the many reasons to appreciate Lúnasa is that even when they’re not performing or recording as a full band, they cultivate opportunities to play together in smaller combinations. Flute and whistle player Crawford has often teamed up with the group’s uilleann piper, Cillian Vallely, for instance, and here he has joined with fiddler Farrell and guitarist Doocey to make an album brimming with excellent musicianship (of course), abundant good cheer, and the same creative spirit that energizes Lúnasa in its full incarnation. And in the same vein, grounded in tradition though the trio may be, “Music and Mischief” shows the contemporary mindset in their music, not least in their repertoire.

In one set, the three begin a with an elegant, festive Galician tune, “Pasacorredoiras do Condado,” and then launch into a pair of contemporary polkas, “The Corner House” (by Aidan Coffey) and “Ned Kelly’s” (by the musician of the same name). A pair of jigs, “Taylor Bar 4 a.m.” (by fellow Lúnasan Donogh Hennessy) and Michael Goldrick’s “Ceol na Mara,” features Farrell pairing with Crawford on whistle, offering a glimpse of that distinctive layered, harmonic Lúnasa sound. The twin whistles also are at the forefront of the aptly named “Pure Irish Drops” set, beginning with Carmel Gunning’s jig “Road to Maugheraboy” – with a lovely bouzouki backing by guest Alan Murray – and segueing into the traditional reel “Moneymusk” and Charlie Lennon’s “The Dowry.”

Crawford’s slow reel, “The Headspinner,” exhibits his ability as a tune composer as well as the outstanding control and precision in his flute-playing, as does the reel that follows, Pat Walsh’s “The Teacake.” Doocey exhibits his lithe, melodic playing at the outset of his composition, “The Road to Foxford,” which Crawford’s flute then picks up, Doocey switching to a jazz-flavored accompaniment enhanced by Stephen Markham’s electric keyboard; then Farrell enters on “Wade’s Reel,” one of his many originals on the album, Jonny Hulme’s five-string banjo joining the mix.

Crawford does a fascinating solo whistle take on an 18th-century classical piece, Ferdinando Carulli’s “Opus 34 Duo in G,” Doocey providing an appropriately drawing-room-type backing. Farrell’s showcase is an epic medley of his own tunes, the jig “Head First” and reels “Night Heron,” “The Happy Shadow” and “The Wild Lime,” Hulme’s banjo helping engineer a gradual shift into a newgrass mode, with Farrell firing off hot bluegrass licks and jazz-like improvisations.

But don’t regard “Music and Mischief” simply as a stop-gap until the next Lúnasa release: It deserves to be listened to, and savored, on its own terms. [tinyurl.com/musicandmischief]

Steeleye Span, “Est’d 1969” • In a year chock full of 50th anniversaries (the moon landing, Woodstock, Monty Python, “Sesame Street,” “The Brady Bunch,” The Gap and ATMs, to name a few), there’s a very significant one where Celtic/folk music is concerned: Steeleye Span.

Steeleye was, along with Fairport Convention and Pentangle, a foundational force in the British folk revival. The band – particularly in its early years – showed a steadfast commitment to traditional music even as it experimented with electric guitars and bass (not to mention electric dulcimer) and eventually drums, and contemporary-minded arrangements that grew increasingly sophisticated. Their repertoire covered not just rural and maritime folk songs but the older, literary ballads, especially those of the supernatural ilk (“King Henry,” “Allison Gross,” “Thomas the Rhymer,” “Twa Corbies,” “False Knight on the Road”) and songs of ritual and ceremony (“The King,” “Gower Wassail,” “Gaudete”), with the occasional set of Irish jigs and reels. Steeleye’s ranks have included a number of prominent, influential figures in the folk revival, notably Martin Carthy, future Pogue Terry Woods, John Kirkpatrick, Peter Knight, and, of course, lead vocalist Maddy Prior.

There were periods when Steeleye was dormant, or all but done, what with personnel changes, and members’ other musical activities and priorities. And the band’s shift to a more conscientiously rock, and commercial, sound and focus on original material may have produced some sales-measured success – namely their hit single “All Around My Hat” – but did not always sit well with many long-time fans or music critics.

Yet here they are still, with their 23rd studio album and fourth in the last 10 years. “Est’d 1969” recalls some of the same virtues that marked their earlier work: “Harvest,” a medley of two original songs, features the group’s trademark harmony vocals and celebration of rustic traditions a la “The King” and “A Calling-on Song”; “Mackerel of the Sea” and “Cruel Ship’s Carpenter” are of a piece with their long list of classic, deftly arranged ballad adaptations; and another medley, “Domestic,” dips into the store of comic – sometimes darkly so – songs about male/female relationships, in the manner of “Marrowbones” and “Four Nights Drunk.”

As a founding member, Prior herself, now 72, is a link to those past years and simultaneously a symbol of Steeleye’s fortunes, for better and worse, over five decades: During the mid-1990s, she began experiencing difficulties in her vocal range and shortly thereafter took an eight-year sabbatical from the band to pursue other projects. Her voice has mellowed and deepened over time, and no longer hits the high notes of a “Gaudete,” “Sheepcrook and Black Dog” or “The Weaver and the Factory Maid.” But she compensates very well, leaning more on her role as storyteller than folk chanteuse, such as in “Mackerel of the Sea,” or embracing a sultry tone in “My Husband’s Got No Courage in Him” – the second, more scurrilous part of the “Domestic” medley. The band has always made space for their other vocalists, anyway; one stand-out here is bouzouki/guitar/banjo/mandolin player Benji (son of John) Kirkpatrick, who leads on “Cruel Ship’s Carpenter.”

From a purely musical standpoint, this version of Steeleye also fares pretty well. Dublin-born drummer Liam Genockey, on his second tour of duty with Steeleye, has been praised for his adventurous flair, and guitarists Andrew Sinclair and Julian Littman (he also plays mandolin and keyboards) adroitly handle rhythm and lead. Jessie May Smart, who had the unenviable task of succeeding Peter Knight, is more violinist than fiddler, yet she can simulate trad-like lines and phrases as necessary; her style also works with the elaborate, progressive rock-type interludes in some of the songs, notably “Old Matron,” which is further enlivened by a cameo from flutist Ian Anderson of Jethro Tull.

Not everything works. The rendition of an Arthurian ballad, “The Boy and the Mantle (The Three Tests of Chastity),” comes off as rather twee and overly arty, especially with a harpsichord backing. The arena-rock accompaniment to “My Husband’s Got No Courage in Him,” complete with wah-wah guitar, almost overwhelms Prior. Their setting of a 1910 John Masefield’s poem “Roadways” seems unbecomingly gauzy.

It’s a fact of life that bands can and do change by necessity or inclination, especially over such a long stretch, and maybe holding them to past standards is unrealistic, even unfair. But long memories can be inconvenient: For some Steeleye aficionados, the period between, say, “Please to See the King” and “Parcel of Rogues” still stands as their strongest, almost perfectly balanced between folk and rock.

Yet if there are disappointing moments on “Est’d 1969,” the final track provides some redemption. “Reclaimed,” written by Prior’s daughter, Rose-Ellen Kemp, is about the ephemerality of man-made creations, of the tensions and sadness wrought by modern life, and our innate ability to fill the void. Steeleye sings it in exquisite a cappella harmony, and it’s almost impossible not to think of similar items in their lengthy discography that evoked green and pleasant lands of times past. Not a coda for Steeleye, perhaps, just a contemplation of future days. [steeleyespan.org.uk]