December 1, 2022

Anthony Quigney, “Breath-Taking”; Draíocht (June McCormarck & Michael Rooney), “Tobar an Cheoil” • Apologies for the lack of attribution here, but somebody – somewhere, at some time – once observed that the flute could be considered one of the more intimate of the instruments used in Irish music, since it’s powered directly by the very breath of the person playing it (obviously, the same could be said for the tin whistle, but that’s another story). That’s as good as any explanation for why the Irish flute, in the right hands, can exert such a powerful hold over the listener: You could say the flutist is literally putting him/herself into the music, giving the flute a unique kind of soulfulness.

Boston-area flute/whistle player Shannon Heaton recently shared her thoughts on the flute’s presence in Irish traditional music. “Whatever the instrument, Irish tunes are best when they are conveyed with care. With a clear presentation of the melody. With thoughtful phrasing. Flute players do this, in part, with where we breathe, and how we breathe, and pause, with the people we are playing with.”

She added, “It’s very exciting to hear strong and lively rhythmic flute playing. But no matter the speed, the deepest and most nourishing Irish flute playing features a rich straight tone, superb intonation, gorgeous rhythmic style, and clean mechanics with sensible and interesting phrasing.”

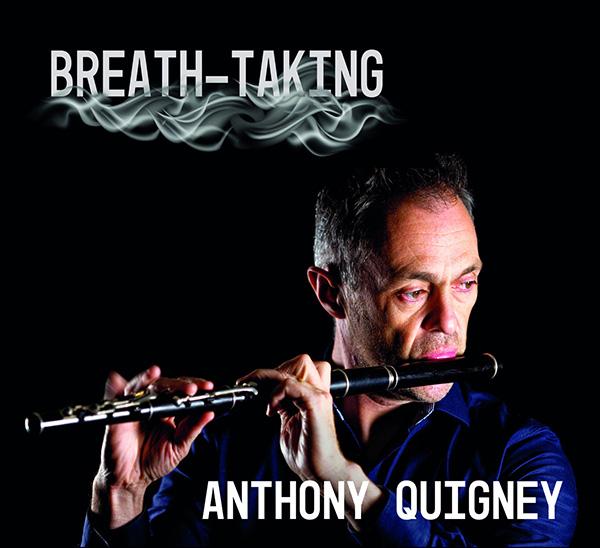

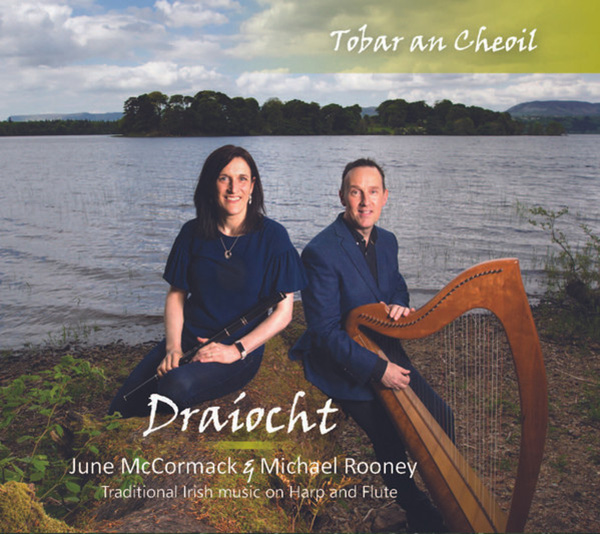

Heaton’s words are worth keeping in mind with the release of two albums in recent months that offer an opportunity to consider the essence and nature of the flute in Irish music. Clare native Anthony Quigney will be familiar to fans and friends of the venerable Kilfenora Ceili Band, which he joined in 1992; this is his first solo album – he and fiddler Aidan McMahon recorded “A Clare Conscience” in 2006, which suggests he has a thing for droll album titles. “Tobar and Cheoil” is the third release for June McCormack and harpist Michael Rooney as Draíocht. McCormack, from Sligo, is a former senior All-Ireland flute champion and TG4 “Young Musician of the Year,” while Monaghan’s Rooney – the TG4 “Composer of the Year” for 2017 – has published suites for solo harp and harp with ensemble/orchestra.

On “Breath-Taking,” Quigney’s flute is featured in various combinations with guest musicians including his son Aidan and sister Marie (both on piano), fellow Kilfenora bandmates cellist Sharon Howley and fiddler Eimear Howley, as well as guitarist Conal O’Kane, bassist Brian O’Grady and Dermot Sheedy on bodhran. This makes for a pretty diverse range of textures throughout the course of the album, such as on the opening medley of jigs, with O’Kane’s punchy backing undergirding “Banish Misfortune” while Marie Quigney adds some quiet chording, gradually building to a more constant rhythm when Anthony transitions into “Frawley’s Jig,” finishing up with Peadar O’Riada’s gem “Spórt” – a showcase if ever there was one (the third part especially) for a flute player’s control and phrasing, and Quigney is spot on.

Sheedy’s bodhran brings a steady pulse beside Quigney’s flute to another set of jigs, “The Snowy Path/Bean Pháidín,” which gets a lift on the second of these from Howley’s cello and Quigney’s added whistle. A trio of reels – “A Parcel of Land” (Charlie Lennon)/The Maids in the Meadow/The Caucus Reel (Jean Duval)” – is more on the spare side, primarily Quigney with O’Kane and Sheedy, and the flute-guitar combo is in especially splendid form on the middle tune. For a contrast, strings, piano and a subtle bodhran form a gentle backdrop for Quigney’s slow reel “Time Flew,” led by both flute and whistle; he wrote it on the occasion of Aidan’s finishing school, one of those milestones that typically inspire an emotive parental response.

Also deserving of notice is Quigney’s excellent rendition of “Colonel Frazier” (sometimes cited as “Fraser” or “Frasier”), which he dedicates to his flute teacher Matt Molloy; it’s historically been referred to as a piping tune, but in recent decades Molloy and others – including Quigney – have shown that flute has the musculature to handle the onslaught of triplets in the third part.

“Tobar an Cheoil,” of course, is not a McCormack solo flute album, but very much a joint effort with Rooney, who composed many of the tunes they play on the recording. While flute-centric albums often feature rhythm instruments like guitar or bouzouki, or other melody instruments (fiddle, banjo, etc.), a harp can fulfill both roles, especially in the capable hands of someone like Rooney. What’s more, the tonal qualities – the resonance of wood-and-strings alongside the flute’s breathiness – are an acutely striking combination.

One particularly appealing track comprises a pair of jigs by another flute player of renown, John Brady, former leader of the Longridge Ceili Band, which won All-Ireland titles in the late 1970s and early ’80s: McCormack is in the forefront on “Fr. John’s Jubilee Jig,” Rooney lending a brisk, snappy rhythm; Rooney joins in on the melody for “McIntyre’s Fancy,” and the way they both play through the accented phrase in the B part is a nifty bit of work. They also excel on a selection of robust reels, “Come West Along the Road” and “The Boys of Ballisodare” – not to be confused with the hop jig of the same name, which they do in a medley with Rooney’s “The Devil’s Chimney.”

The pair are joined by guest musicians on assorted tracks, including guitarist Seamie O’Dowd on Rooney’s “An Cruitire,” and to great effect by cellist Aoife Burke and violinists Maria Ryan and Lucia MacPartlin on Rooney’s sublime planxty “He Wishes for the Cloths of Heaven” (inspired by the W.B. Yeats poem) and “Reconciliation Jig.” There’s a similarly elegant feel to Rooney’s “Planxty Castle Leslie,” and here McCormack really shows a considerable range and precision.

All told, both albums exhibit the virtues Heaton mentions, especially the one about tunes being conveyed with care whatever the instrument, be it flute, harp, fiddle, accordion or tenor banjo – perhaps even Moog synthesizer.

Brighde Chaimbeul, Ross Ainslie and Steven Byrnes, “LAS” • It’s a pretty basic set-up: Chaimbeul and Ainslie play Scottish smallpipes in the key of C, in duet or harmony, with Byrnes lending support on guitar or mandola. But that doesn’t even begin to describe how powerful and ambitious this album is, in concept and execution, nor the high level of musicianship these three exhibit, individually and together.

Considering the pedigree of those involved, that’s not exactly a surprise: Chaimbeul, from the Isle of Skye, has won prestigious BBC Radio 2 awards, including Young Folk honors, on the strength of her first release, “The Reeling” (her sister Màiri, by the way, is an excellent harpist who studied and taught at Berklee College of Music for several years); Ainslie has been an innovative force on the Scottish folk music scene for some years now, whether on his own or playing with the likes of Dougie Maclean, the Treacherous Orchestra, Shooglenifty and Salsa Celtica; Byrnes, who also is a drummer (though not here), has collaborated and performed with numerous folk/trad artists including Kate Rusby.

Most of the tunes on “LAS” are of Scottish origin, whether traditional or contemporary, including originals by Ainslie and Chaimbeul. Ainslie’s works make up three of the four tunes in the album’s opening – and definitively tone-setting – track “The Green Light Set,” which starts with the air “Green Light of the Lonely Souls,” as devastatingly doleful as the title implies and offering an introduction to all matter of masterful piping techniques by Chaimbeul and Ainslie, especially their ability to slowly and unerringly slide from one note to another. Then the pace picks up with the first of three reels, “Bob the Banter,” and the entry of Byrnes on mandola; he ratchets up the rhythm as the trio transitions to the minor-key “Peel Pier Fear” and then – as if emerging from a dark tunnel into the sunlight – they sprint into Damien O’Kane’s ebullient “Castlerock Road.”

Plenty more superb Scottish content follows (notably the “Strathspeys and Reels” and “John Patterson’s Mare” tracks, and Chaimbeul’s charming “The Badger and the Weasel”) but “LAS” also encompasses other music traditions: a bracing medley of Irish reels; a spellbinding selection of Breton gavottes; a driving Asturian tune; and not one but two sets of Bulgarian dances – the first of these includes a jaw-dropping sequence in which Chaimbeul and Ainslie’s pipes emit rapid-fire pulses that accentuate the characteristic Balkan polyrhythms.

However much well-deserved attention Ainslie and Chaimbeul get, don’t overlook Byrnes’ contributions: He provides the perfect complement of rhythm and harmony, his shrewd use of the guitar’s or mandola’s lower strings filling out the aural spectrum of “LAS” – a quite impressive one it is, too.

[brighdechaimbeul.bandcamp.com/album/las]