October 6, 2022

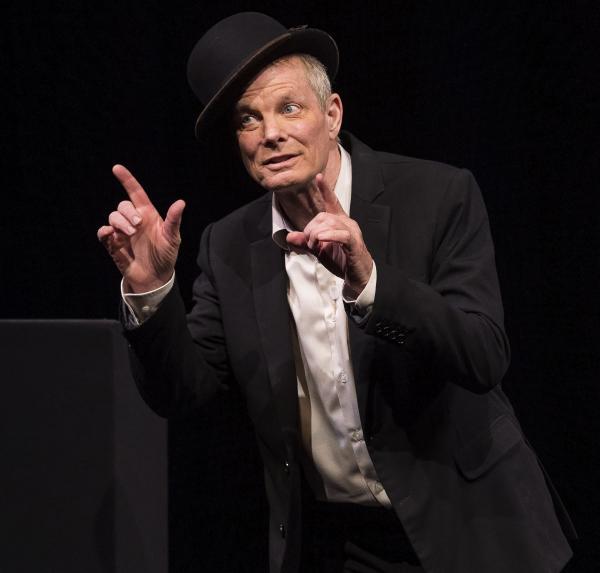

Bill Irwin explores the work of Samuel Beckett in his one-man show, “On Beckett,” at ArtsEmerson, Oct. 26–30. Craig Schwartz photo

Two-time Tony Award winner Bill Irwin is a master actor, director, writer, and clown known for an outstanding body of work crossing stage, film, and television. Most important for Boston audiences, he’s coming to town to share an explanation and exploration of the words of legendary Irish playwright Samuel Beckett.

From October 26-30, he will present his solo stage piece, “On Beckett,” at ArtsEmerson’s Paramount Theatre. He has also been named Emerson’s 2022-23 Fresh Sound Artist in Residence.

Irwin conceived this piece to provide a window into his fascination, frustration, and relationship to the works of Beckett, widely regarded as one of the greatest dramatists of the 20th century. He’ll incorporate passages from Beckett’s “Texts for Nothing,” “The Unnamable,” “Watt,” and “Waiting for Godot,” among others. Irwin premiered the piece at the Irish Repertory Theatre in New York.

Notably, he was the first performance artist to receive a five-year MacArthur Fellowship, commonly known as The Genius Grant. This fall, he will be inducted into the Theater Hall of Fame in New York.

Irwin, who hails from Irish stock, previously starred in Beckett’s “Godot” at Lincoln Center with Steve Martin and Robin Williams. He's also delighted audiences as the baggy pants clown in “Fool Moon,” “The Regard of Flight,” and “Old Hats;” performed Shakespeare, O’Neill, and Albee; appears as Dr. Peter Lindstrom on “Law & Order: SVU;” and charmed young audiences as Mr. Noodle on “Sesame Street’s Elmo’s World.”

He was last seen in Boston repeating his award-winning Broadway role as George –opposite Kathleen Turner’s Martha – in the national tour of “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolfe.”

When we chatted recently by phone, he was at home in New York, preparing for an appearance at a theatre festival in Ireland. Here’s an edited look at our conversation.

Q. What first drew you to Samuel Beckett’s work?

A. I feel like Beckett’s work is a pretty hefty-sized continent which I happened to visit in my youth and have returned to, but still feels fairly unchartered overall.

Q. When was this?

A. I went to school in Belfast over 50 years ago, but it was an important, informative year of schooling. The end of high school. And when I was there, I walked around the hills of Belfast much like Mr. Beckett walked around the hills of Dublin. And so I began to read some of Beckett’s “Texts For Nothing,” where he’s talking about walking around the hills, but he’s also talking about, possibly, the way the brain is shaped, the hill-like structure of the human brain anatomy, and I was hooked. And it’s been a fatal connection.

Q. It became very personal?

A. Something in the Irishness, which is full of irony since he wrote it all in French, but something about the Irishness of the voices and the connection to family . . . I suddenly felt I understood myself much better.

Q. Did you bring the concept for “On Beckett” to Irish Rep, or did they approach you about creating something special for them?

A. I brought it to them because it had been festering inside of me for quite a while. Out in San Francisco, where I lived for a long time . . . I would go to work at American Conservatory Theatre, especially during the years when Carey Perloff was running the theatre. She and I would talk about this, about an evening. I told Carey it’s partly a coping mechanism. I have this language which won’t leave me alone and I need to find out, in my actor’s life, what to do with it. It’s partly a celebration of the language.

Q. Do audiences need to be well versed in Beckett?

A. No, that is one of my great excitements. And if I allow myself a little pride now and then . . . I’ve worked hard to make it an entry to the language. I’ve been greatly complimented when people have said “Yeah, I’ve taught this all my life and I consider myself a Beckett scholar and I enjoyed the evening very much and I’m glad I came.” That’s a great compliment, but really in many ways, it’s retracing my entry to the writing. And so, no. No knowledge of his work is needed.

Q. I understand you actually met Beckett.

A. I was so paralyzed with shyness. And he was a shy man, too. That’s one of the things that struck me. We sat across from one another. It was in the last year and half of his life . . . It was sort of a courtesy call set up by a literary friend who had gotten to know him. Here’s the thing about Mr. Beckett. He was austere. He was sort of removed. At the same time, he was a party animal. People would say – (and) I was much too shy to have this happen -- but people have said, “Oh yeah, I got in touch with him and we had drinks and it was three o’clock in the morning and we were walking home from the bar” . . . That was not my experience. I looked at the table the whole time.

Q. Did he offer any special words of wisdom?

A. I was about to play the role of Lucky (in “Godot”), and he said – this is so intriguing – he said to me, the best Lucky ever was an American . . . But whether he was trying to be gracious, which is what he was known for, or whether that really was his favorite interpretation, he had seen an American actor do Lucky and I took great heart at the thought that maybe I had a chance.

Q. Do you find that younger people attending the show may have first been introduced to you as Mr. Noodle?

A. It can happen. It can happen. (Laughs.) I meet young students of various kinds under different circumstances. And every once in a while . . . someone will say, “Excuse me, you were Mr. Noodle?” And it opens up a whole line of inquiry and reminiscence . . . It was a brilliant character and I take no credit. There was a wonderful producer at “Sesame Street” who’s no longer with us – Arlene Sherman was her name – and she said “I want to create a character where the kids are actually better equipped at life than the character. And he needs their help. And it went from there. Just a brilliant idea.

Q. Final thoughts on Mr. Beckett?

A. He’s always talking about the human. And that is his glory.

•••

“On Beckett,” Oct. 26 - 30, ArtsEmerson.org or 617-824-8400