June 16, 2023

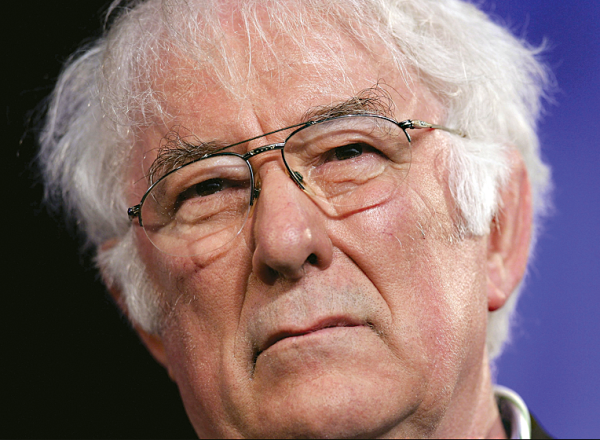

Photo courtesy Notre Dame, South Bend, Indiana

During my long and rich teaching career (1984-2019) at UMass Boston, I had the rare good fortune of being able to offer, multiple times—both as a graduate seminar and as an undergraduate senior seminar—a course centered on Irish Nobel Laureate Seamus Heaney. As the tenth anniversary of his death, on August 30th of 2013, looms large, I’ve been thinking about the various iterations of that course. Heaney was only 74 years old when he passed away, but he made a lasting mark not just on the Irish literary landscape but also globally—a mark that I tried to take the expanding measure of with my students each semester that I offered the course.

In at least one respect the course description remained the same from the first time I offered it (shortly before Heaney was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1995) until the final time a year or so after his passing. At the heart of our reading his body of work was a question that Heaney himself asked relatively early in his career, in the Foreword to Preoccupations, his first volume of selected prose writings, published in 1978: “[H]ow should a poet properly live and write? What is his relationship to his own voice, his own place, his literary heritage and his contemporary world?”

Needless to say, Heaney continued to write and to publish prolifically during the two decades I taught the course, so his own implicit engagement with that question continued not just to evolve but to morph from his early cultural “excavations” (his word) famously projected in “Digging,” the opening poem in his first volume of poems, Death of a Naturalist (1966): “Between my finger and my thumb / the squat pen rests. / I’ll dig with it.” Following the chronology of his life and his career, the course inevitably tracked the trajectory of Heaney’s writing through the tumultuous years of “The Troubles” in his native Northern Ireland—his grappling as a writer with the implications for his art of living in a country divided and subdivided unto itself—and then proceeded to investigate his inclination in his later volumes toward a more personally lyric engagement with the world: “waiting until I was nearly fifty / To credit marvels,” as he put it. As his output increased exponentially over the decades, I assigned three different volumes of his “selected poems,” the final one being Opened Ground: Poems 1966-1996. He published three more standalone volumes after that—Electric Light (2001), District and Circle (2006), and Human Chain (2010)—which I incorporated into the syllabus as they appeared.

If I were still in teaching harness, I would probably assign the two-volume set of Selected Poems (1966-1987 and 1988-2013) published in paperback in 2014. But nowadays when anyone asks me about getting a handhold on Heaney, I usually recommend a single volume, titled 100 Poems, published in 2018. Curated by his family—his wife, Marie, and their three children—this book includes the essentials, starting (of course) with “Digging.” In a “Family Note” at the front of the book, daughter Catherine explains that “the notion of a ‘trim’ selection” appealed to her father but acknowledges that the compilation decided on by her and her mother and her two brothers comprises not just his preferences but some of theirs as well: “It includes many of his best-loved and most celebrated poems, as well as others that were among his favourites to read and which conjure up that much-missed voice. However, we made some choices that have special resonance for us individually: evocations of departed friends; remembered moments from a long-ago holiday; familiar objects from our family home.”

Although the selections appear chronologically, they are not identified by specific volumes. In a sense this is liberating for both newcomers to Heaney’s work and seasoned readers alike: while several of Heaney’s individual volumes of poems are organized around an obvious thematic center, 100 Poems invites the reader to engage with the poems one by one and not even necessarily in the order in which they appear—the effect will be cumulative . . . but there will be no final exam at the end! In fact, reading around in 100 Poems can produce a sort of connect-the-dots effect: the “picture” of Heaney that emerges may be that much more personal for each reader.

Probably, however, most readers will recognize that certain poems add conspicuous shading to that picture. An early poem like “Personal Helicon,” for example, translates a childhood fixation with literal murky wells into a metaphor for the poet’s grown-up commitment to his art: “I rhyme / To see myself, to set the darkness echoing.” Likewise, the sensuous final line of “Bogland”—“The wet centre is bottomless”—inscribes the promise of poems that Heaney elaborates on in his seminal essay “Feeling Into Words”: “poetry as . . . a dig for finds that end up being plants.” And that, in turn prepares the reader for the implications of “The Tollund Man,” which introduces Heaney’s fascination with the recently exhumed bodies sacrificed to a territorial “Mother Goddess” in Iron-Age Denmark: those bodies would become, in his volume North (1975), “befitting emblems” for trying to comprehend the essence of the sectarian violence devastating contemporary Northern Ireland. Describing “The famous // Northern reticence, the tight gag of place / And times,” another poem from that volume yielded what has become a household expression: “Whatever you say say nothing.”

But poems like those and the thematic weight they carry are leavened throughout 100 Poems by lyrics like the simply titled “Song,” that closes with the much-quoted phrase “the music of what happens,” and “domestic” poems like “The Otter,” in which the poet admires his wife dripping wet after a swim—“Heavy and frisky in your freshened pelt”—and “The Skunk,” in which a nighttime visitation outside his window during a sojourn in California reminds him of her “head-down-tail-up hunt in a bottom drawer / For the black plunge-line nightdress.” A different sort of intimacy is shared in his sonnet remembering how, in his mother’s final moments, he recalled peeling potatoes with her in their farmhouse kitchen: “I remembered her head bent towards my head, / Her breath in mine, our fluent dipping knives— / Never closer the whole rest of our lives.”

Another sonnet (Heaney was a master of that fourteen-line form), titled “The Skylight,” celebrates how “when the slates came off, extravagant / Sky entered and held surprise wide open.” A similar spirit of wonder infuses a twelve-liner recounting the tale of how a crewman from a sailing ship appearing in the air above the ancient monastic settlement at Clonmacnoise, after receiving assistance from the monks to free the ship’s anchor hooked into the altar rails, ultimately “climbed back / Out of the marvelous as he had known it.” Ditto for the prevailing spirit of “St Kevin and the Blackbird,” set at the monastic settlement of Glendalough: “And since the whole thing’s imagined anyhow / Imagine being Kevin.”

100 Poems also includes “Postscript,” which many of Heaney’s readers and admirers turned to when news of his death broke in 2013, finding uplift in its invitation to be pervious to the “big soft buffetings,” felt by the poet on a windy drive in the west of Ireland, that can “catch the heart off guard and blow it open.” (My personal go-to poem at the time was “The Harvest Bow.”) The book includes “The Gravel Walks,” too: two years after his death, a phrase from the closing stanza of that poem would be incised on Heaney’s permanent gravestone in St. Mary’s cemetery in Bellaghy in south County Derry: “walk on air against your better judgement.”

Thumbing recently through 100 Poems, I paused about a dozen pages from the end over a three-poem sequence titled “Chanson d’Aventure.” Included in his final volume, Human Chain, the sequence opens with a description of the immediate aftermath of a stroke Heaney suffered in 2006: “Strapped on, wheeled out, forklifted, locked / In position for the drive . . .” In one respect this can be read readily as the poet’s intimation of his mortality. But both in addressing his wife directly in the poem and in directing her—and the reader—up the page to the poem’s epigraph, two lines from “The Ecstasy,” a poem by 17th-century British poet John Donne, Heaney allows that not only his love for Marie but also his abundant output of poems may endure: “Love’s mysteries in souls do grow, / But yet the body is his book.”

Thomas O’Grady was Director of Irish Studies at the University of Massachusetts Boston from 1984 to 2019. He is currently Scholar-in-Residence at Saint Mary’s College in Notre Dame, Indiana.