September 30, 2020

The brief meeting was one of titans. One was a Black abolitionist and escaped slave on the rise, the other an aging, legendary statesman dubbed Ireland’s “Liberator.” A mythic description of the moment that Frederick Douglass and Daniel O’Connell crossed paths in Dublin would sprout up; however, the encounter proved to be hardly as dramatic as admirers of both men would have it. Still, the impact of that moment was profound for Douglass, shaping in several key ways his determination to remove the shackles of slavery in the United States.

In 1818, Frederick Augustus Douglass was born a slave in Maryland in 1818, his father a white man. He would only see his mother a handful of times. Douglass was also that rarity of the Antebellum South, illegally taught to read and write by his owner’s wife.

Perhaps fittingly, it was a local pair of Irish laborers who planted the idea of escaping to the North in the young slave. He did just that at the age of 20, knowing full well he could be seized by slave-catchers at any point and dragged back south. A gifted speaker and writer, he soon garnered widespread attention and acclaim by abolitionists for his eloquent jeremiads about the evils of slavery. His public star ascended even further when William Lloyd Garrison, one of the foremost abolitionists of the era, enlisted the brilliant former slave to hit the lecture circuit.

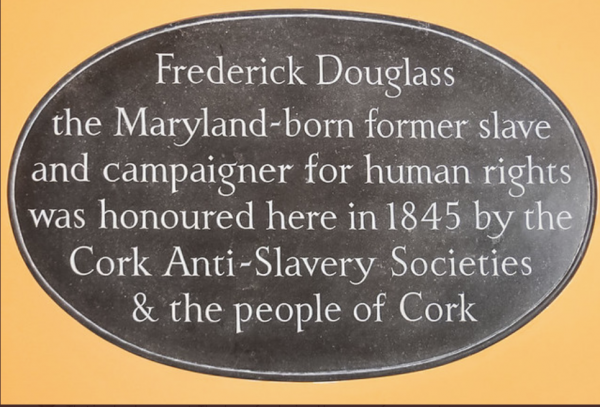

Douglass published his autobiography, “The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave,” in 1845, and while it earned him fame coast to coast, the publicity also unleashed incessant threats to his life, as well as the grim prospect of being seized by slave-catchers, and led to a momentous decision by Douglass and his supporters. He boarded a ship to Ireland and landed on Aug. 31, 1845, to meet with abolitionists there and in England.

As the eminent historian and author Dr. Christine Kinealy notes in her expert studies of O’Connell and Douglass, the relief in the fugitive slave’s own words upon his arrival in Ireland was palpable: “I am now safe in old Ireland, in the beautiful city of Dublin.” The well-known abolitionist Richard Webb, hoping to publish Douglass’s autobiography for an Irish readership, persuaded him to remain longer in the city than he had planned.

Douglass made a splash in the city, the newspapers and locals captivated by his striking appearance and eloquence. There was at the time another noted orator in the city who was world-renowned as an ardent foe of slavery, poverty, and inhumanity of every ilk. His name was Daniel O’Connell.

In any Hollywood script, a memorable, highly charged meeting between the young lion of abolition and the old lion of human rights would have to unfold. After all, O’Connell had organized mass protests of Ireland’s impoverished Catholic masses into “monster” rallies that had struck terror in Britain’s Parliament. The architect of “Catholic Emancipation,” he had also played a pivotal role in finally ending slavery in in every corner of the British Empire and was still futilely fighting for Repeal of the Union between Britain and Ireland. His spellbinding speeches were virtually unrivaled by any other statesmen of the century. Garrison described O’Connell as “the distinguished advocate of universal emancipation, and the mightiest champion of prostrate but not conquered Ireland.”

Fifty years later, after Douglass’s death, a friend of his would claim that the fugitive slave, then 27, and O’Connell, 70, had met as follows at the Irishman’s home, in Merrion Square: “Douglass had a letter of introduction from Charles Sumner, but when O’Connell’s servant announced that there was a colored man at the door, the great Irish-man rushed out and clasping Douglass in a warm embrace, said: ‘Fred Douglass, the American slave, needs no letter of introduction to me.’”

As dramatic and stirring as the account was, and is, there is no other evidence to support the claim. The only corroborated meeting between the two men is quite different.

Douglass himself said that even as a slave he had heard about O’Connell as a fierce opponent of slavery, and in Dublin, he took the opportunity to attend a “Repeal” meeting at Conciliation Hall in hopes of hearing the Liberator speak. He managed to work his way through the gathered throng and into the building. What he heard, he said, changed the arc of his career: “I have heard many speakers within the last four years – speakers of the first order; but I confess, I have never heard one by whom I was more completely captivated than by Mr. O’Connell. . . . It seems to me that the voice of O’Connell is enough to calm the most violent passion. . . . There is a sweet persuasiveness in it, beyond any voice I ever heard. His power over an audience is perfect.”

As the event ended, Douglass was introduced to O’Connell, and only a few words were exchanged. Asked to deliver remarks from the podium to the thinning crowd, Douglass said, “The poor trampled slave of Carolina had heard the name of the Liberator with joy and hope, and he himself had heard the wish that some black O’Connell would yet rise up among his countrymen and cry ‘Agitate, agitate, agitate!’”

In time, Douglass would often be referred to, sometime by himself, as the “Black O’Connell.” Dr. Kinealy notes: “However, the real significance of this phrase is what it reveals about Douglass’s appeal for black people to take responsibility for their own liberation.”

O’Connell, who died some two years after the short encounter with Douglass and as the Great Famine gutted any lingering hopes of Repeal, surely would have marveled at the impact that the American had on the bloody struggle toward the ever-elusive “more perfect union.” Both titans preached the gospel of peaceful protest and unrelenting commitment to human rights. Today, in the United States, politicians and the populace would do well to consider the Liberator’s following words: “Nothing is politically right, which is morally wrong…”

(For further reading, this writer strongly recommends “Frederick Douglass and Ireland: In His Own Words,” and “Daniel O’Connell and the Anti-Slavery Movement,” both works by Dr. Christine Kinealy and available on Amazon)